From the 2018 exhibition catalogue, Tephra ICA

Written by Lily Siegel, Curator

From A to B

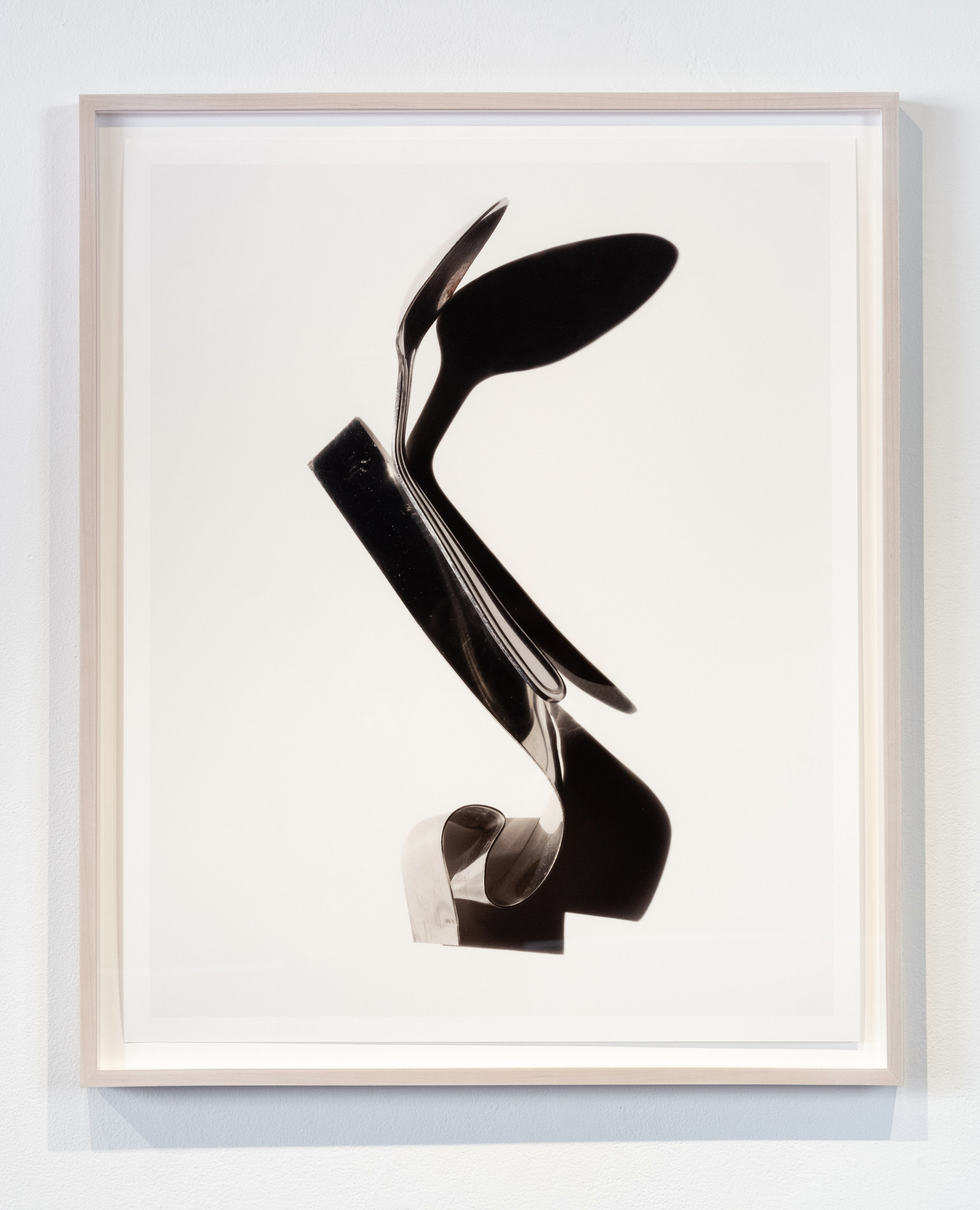

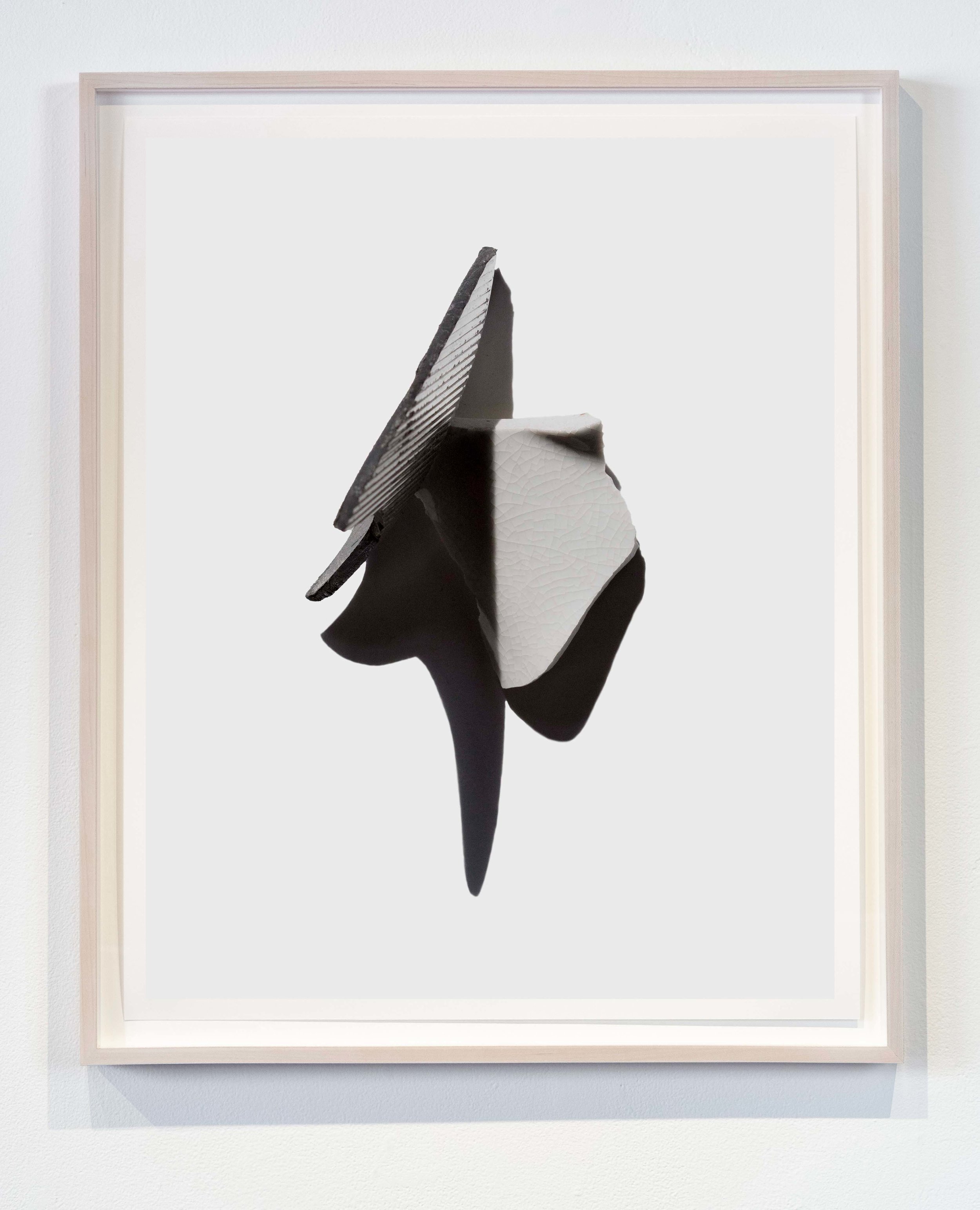

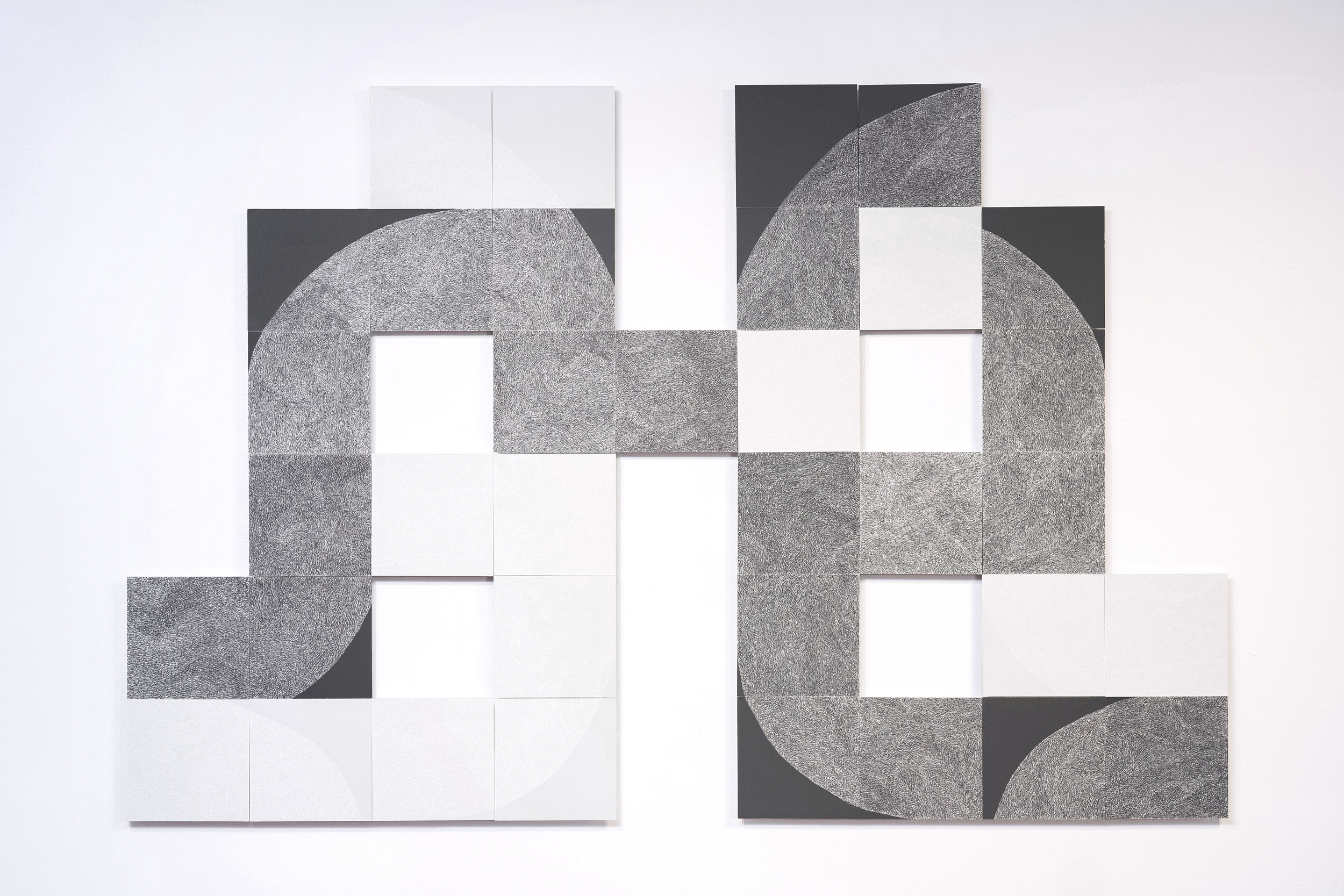

Illuminating the obscured background of our lives is of primary interest to Caitlin Teal Price. Her recent drawing Circadian Drive (A to B in 35 squares) (2018) is a depiction of the route she drove every weekday for three years. She drew with her eyes closed. “Green is the secret color to make gold,” the title of this exhibition, is a phrase repeatedly recited by the artist’s 5-year old son to his younger brother to convince him that green should be his favorite color. Note the alchemical allusion to the possibility of the ordinary becoming extraordinary. The spoons and metal, plastic, and porcelain elegantly posed in her photographs were found on routine walks taken as a young family, thrust into pockets without thought of purpose or value.

Price has primarily been recognized as a photographer of portraits and of places. She has turned her attention and camera on the way others present themselves while managing to slyly amplify that which they are trying to keep hidden. She has put herself in uncomfortable positions to put her subjects at ease. The most recent body of work offers a new perspective on her oeuvre to date. Routine, from the French word for road, has always been a part of her practice. For her series Motel (2002), she documented the interior of roadside motels, sometimes occupied by women selected by the artist, sometimes reflecting occupants just out of view; Northern Territory (2006) depicts lives full of expectation of what may be just around the corner, a liminal state empty of optimism; Annabelle, Annabelle (2009–2012) takes the road as its subject and as its object—women are posed alongside freeways, parking garages, overpasses, and street-side facades.

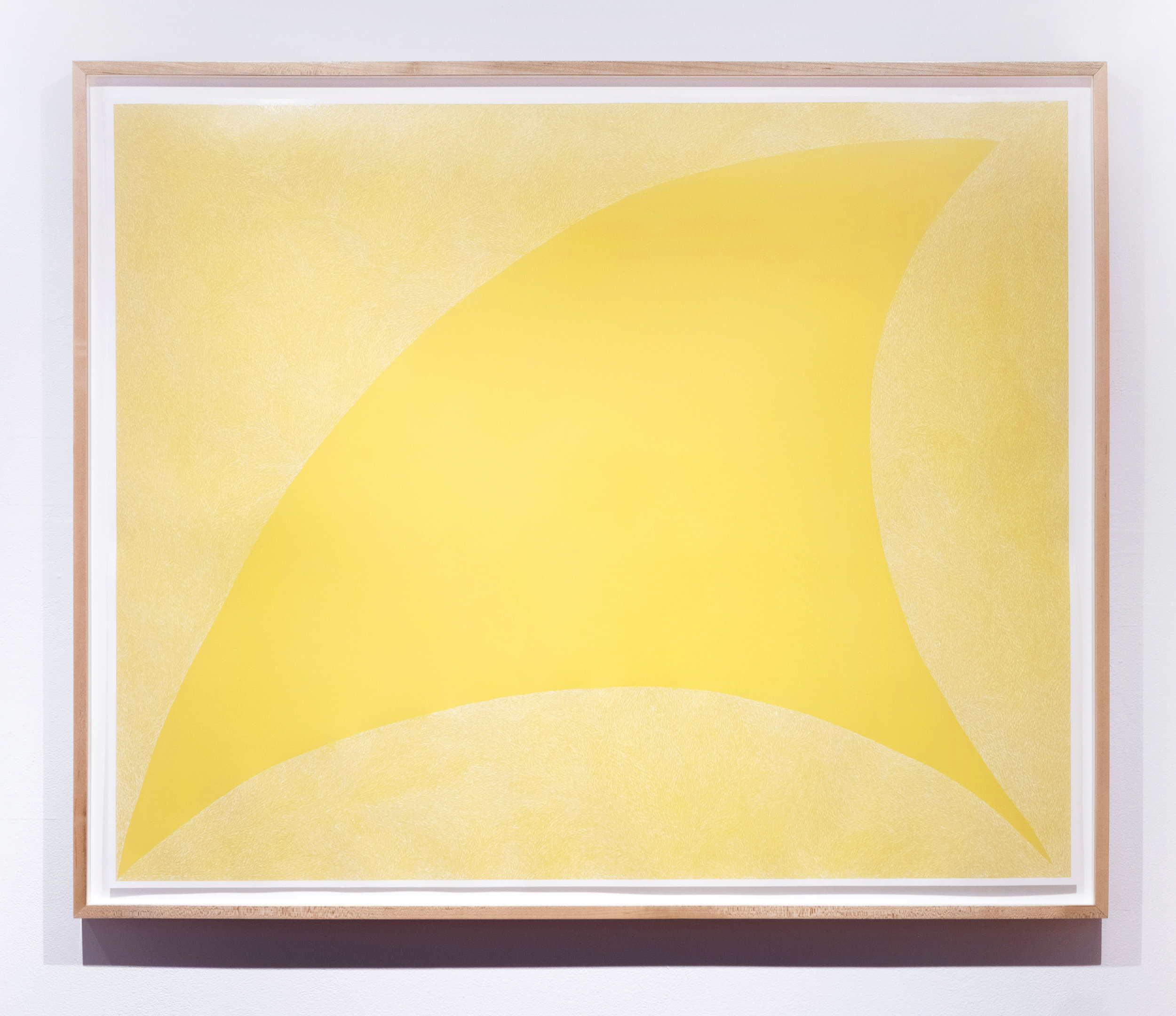

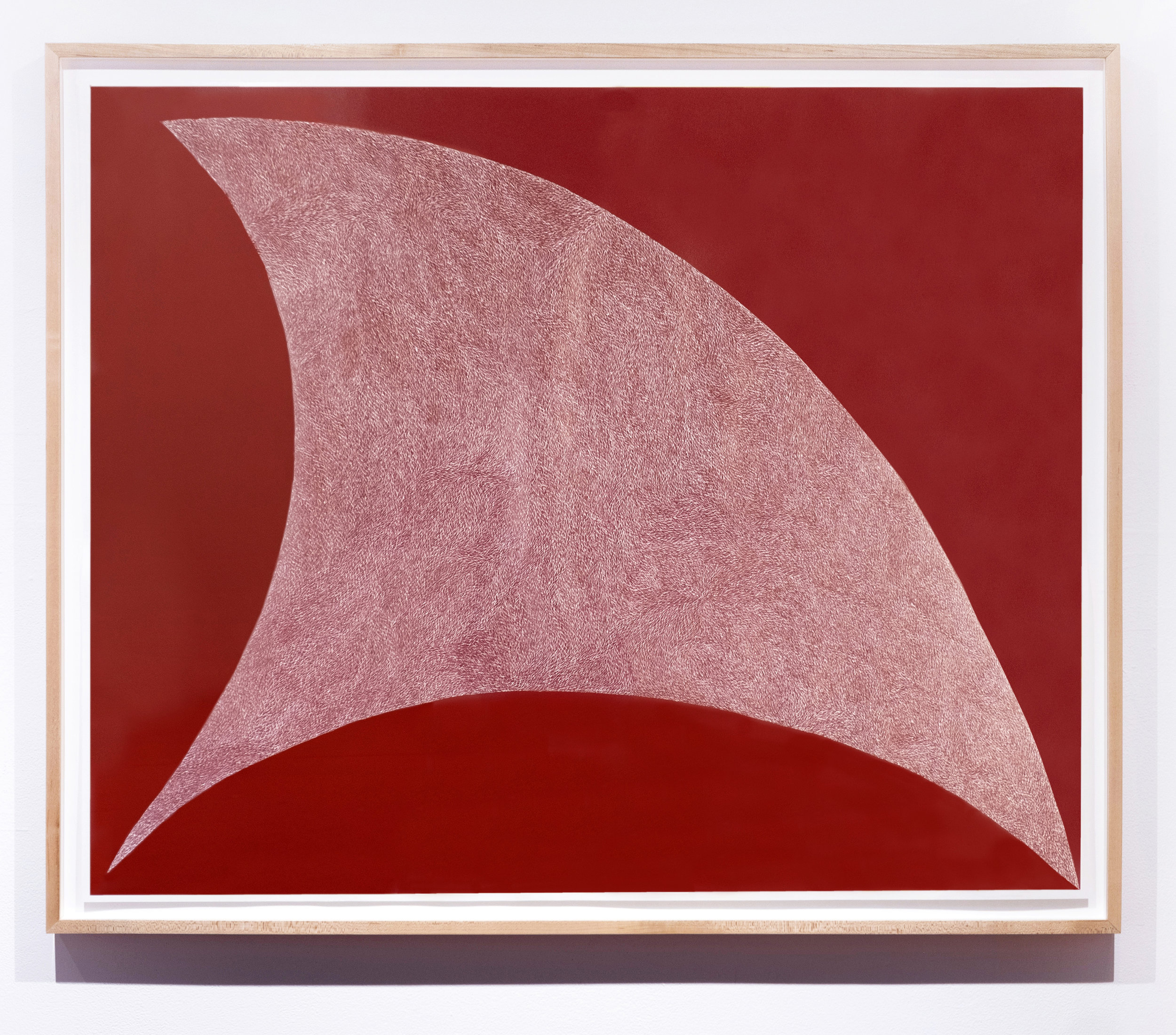

In the newest work, a different path emerges. Price’s most recent series, Collection (2017–2018), and the accompanying drawings in this exhibition serve as a memoir of this moment in the artist’s life. After making Stranger Lives (2008–2015) and publishing her first book, of the series, Price found herself away from New York, settling into life in Washington, DC, and with a studio for the first time ever. Admittedly, it took her three years to figure out how to be productive in this new setting. She simultaneously had less time to herself, as she was a new mother, and more time to spend alone in a space dedicated to her art making. Time became something new to explore as she settled into the routine necessary to balance the life of an Artist Mother. She returned to photographing Birds (2008 and 2015) in the archive of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. She started making drawings. The first drawings were simple schematics, pencil on paper, that later became etchings. Though Price made prints, the metal etching plates are what she considers the final work. She found a tactile interest in material and the manual labor of creating things with her hands beyond the use of a camera, the manipulation of light. She began to reflect on her life and routine.

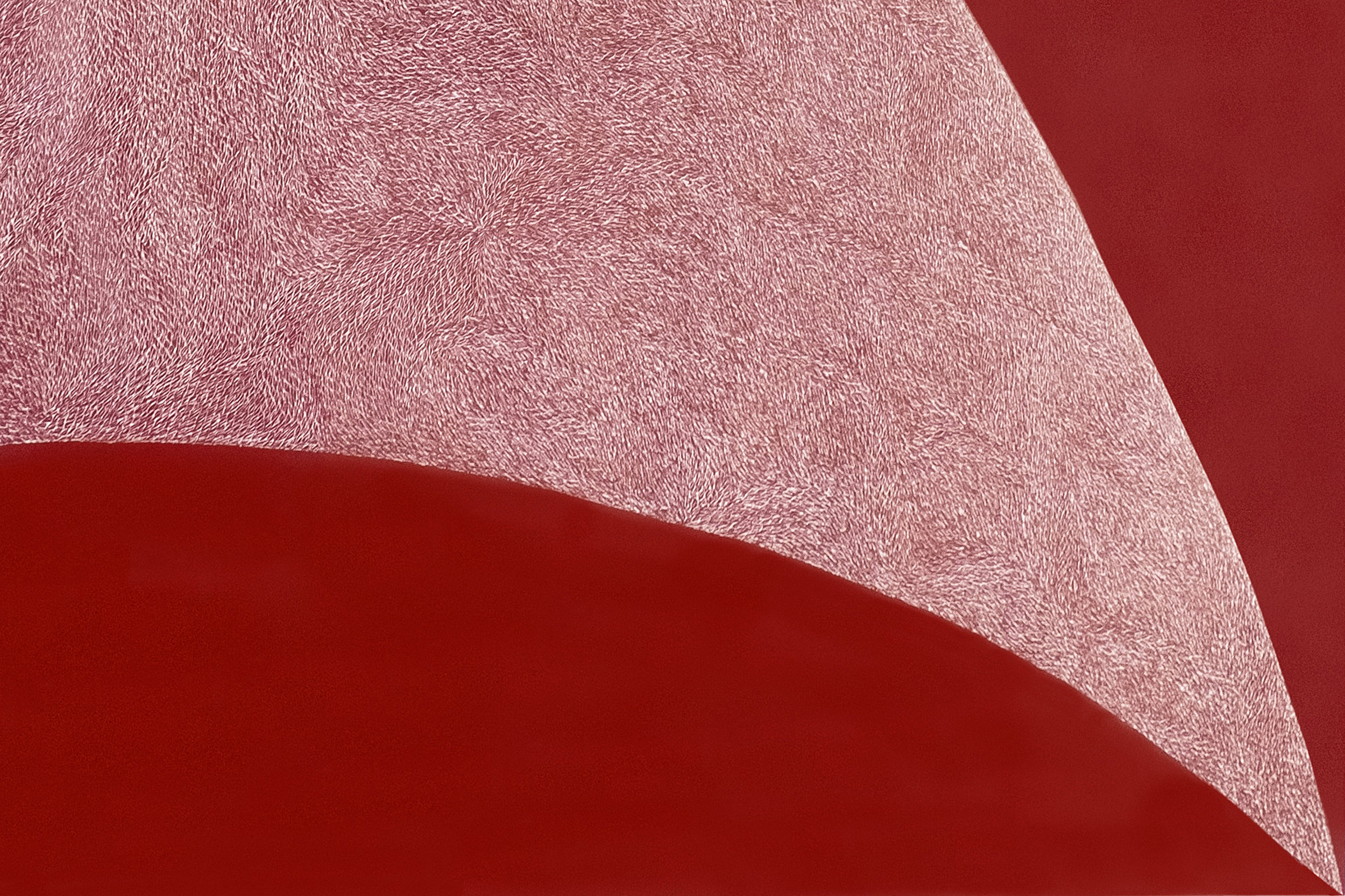

Circadian Drive is reminiscent of David Hockney’s Mulholland Drive: The Road to the Studio (1980). As, Hockney painted his daily drive to the studio from memory, Price drew hers, the drive to her sons’ daycare, with her eyes closed—the title a lovely nod to the daily and the circadian rhythm controlling one’s levels of alertness throughout the day. Both works express a level of comfort and freneticism in the potential of the day. In each, the route becomes an unreliable horizon and the marks of the respective artist’s hand becomes the subject. Color and rhythm express the psychic energies of the drives. Hockney’s colors are jubilant, his marks animated, the joyful anticipation of reaching the studio apparent. Price’s colors are literal, extracted from a photograph of a rosemary bush along the route; her lines are expressions of hard work that add up to an ecstatic composition of satisfied labor.

Work and the labor of artists and parents, especially mothers, is an omnipresent concern in the drawings and the photographs in this exhibition. The images of Collection are directly influenced by Constructivism, the Russian art movement of the 1920s that espoused the conflation of art and life and celebrated technology and “constructed” art. Price found herself rich with discarded objects of technology gathered by her sons and a workspace ready to be utilized. It is easy to read the selection of objects as allegorical—twisted spoons as frustrated attempts at caregiving, the humble stake wreathed in gilded wire and elevated to trophy, the ambulatory wasp astride the coin of no value, porcelain and plastic, the high and low of domesticity. Instead, the story is written by the objects without symbolism. It is a tale of the quotidian. Price has bravely and generously exposed her life to the viewer with a gentle invitation to be self-reflexive and notice the things that define an existence.